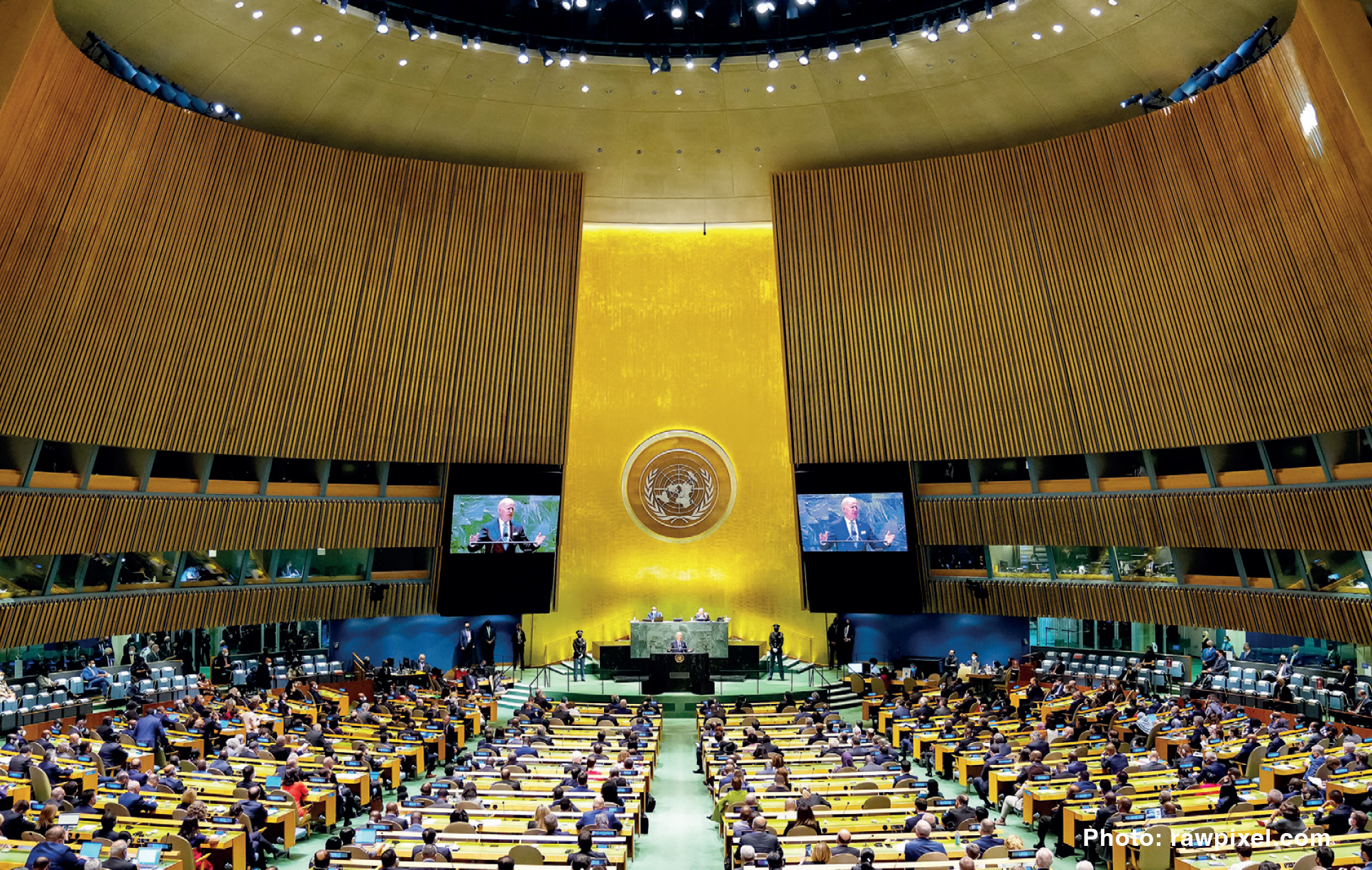

To address these pivotal developments, UN Sec-Gen Antonio Guterres had called for a Summit of the Future to reform our international institutions so that they are fit for purpose in our fast-changing world. —AP

Jeffrey D. Sachs is University Professor and Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and President of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. He has been advisor to three UN Secretaries-General, and currently serves as an SDG Advocate under Secretary-General António Guterres.

Jeffrey D. Sachs is University Professor and Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and President of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. He has been advisor to three UN Secretaries-General, and currently serves as an SDG Advocate under Secretary-General António Guterres.

We are at a new phase of human history because of the confluence of three interrelated trends. First, and most pivotal, the Western-led world system, in which countries of the North Atlantic region dominate the world militarily, economically, and financially, has ended. Second, the global ecological crisis marked by human-induced climate change, the destruction of biodiversity, and the massive pollution of the environment, will lead to fundamental changes of the world economy and governance. Third, the rapid advance of technologies across several domains—artificial intelligence, computing, biotechnology, geoengineering—will profoundly disrupt the world economy and politics.

“We propose […] to establish a “UN Parliamentary Assembly” as a subsidiary body of the UN General Assembly according to Article XXII of the UN Charter”

These interconnecting developments—geopolitical, environmental, and technological—are stoking huge uncertainties, societal dislocations, political crises, and open wars. To address these pivotal developments, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called for a Summit of the Future (SOTF) (September 22-23rd, 2024 at the UN headquarters in New York) to reform our international institutions so that they are fit for purpose in our fast-changing world. Since global peace depends more than ever on the efficacy of the UN and international law, the SOTF should be a watershed in global governance, even if it does no more than point the way to further negotiation and deliberation in the years immediately ahead.

Our existing institutions, both national and international, are certainly not up to the task of governance in our fast-changing world. The late, great evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson, often described our predicament as follows: “We have stumbled into the twenty-first century with stone-age emotions, medieval institutions, and near godlike technologies.” By this he meant that we face our challenges today with the basic cognitive and emotional human nature that was formed by human evolution tens of thousands of years ago, with political institutions forged centuries ago (the U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787), and with the lightning speed of technological advance (think of ChatGPT as just the latest wonder).

Perhaps the most basic fact of deep societal change is uncertainty, and the most basic reaction to uncertainty is fear. In fact, the technological advances—if used correctly—could solve innumerable problems in economic development, social justice (e.g., improved access to healthcare and education through digital connectivity), and environmental sustainability (e.g., a rapid transition to zero-carbon energy sources). Yet the mood today is anything but optimistic, especially in the West. Open wars rage between the United States and Russia in Ukraine, and between U.S.-backed Israel and Palestine. The possibility of war between the United States and China is widely, openly, and even casually discussed in Washington, though such a war could mean the end of civilization itself. At the root of these conflicts is fear, built on our stone-age emotions.

The biggest fear of all is that of many American and European political leaders that the West is losing its hegemony after centuries, and that somehow the loss of hegemony will have catastrophic consequences. Former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson made this Western fear explicit in an April 2024 column for the UK’s Daily Mail, when he stated that if the West loses the war in Ukraine, “it will be the end of Western hegemony.”

Herein lies the essence of the Ukraine war, and many other global conflicts as well. The United States and its allies want to expand NATO to Ukraine. Russia has firmly said no. Both Washington and London were ready to fight a war with Russia over NATO enlargement to protect Western hegemony (specifically, the right to dictate security arrangements to Russia), while Russia was ready to fight a war in order to keep NATO away. In fact, Russia is prevailing on the battlefield over Ukraine’s army and NATO’s armaments. This is not surprising. What is perhaps surprising is how the West completely underestimated Russia’s capabilities.

In broad terms, with the changing global order, including the rise of China and the rest of East Asia, the military and technological strength of Russia, the rapid development of India, and the growing unity of Africa, the Western-dominated world has been brought to an end, not by a tumultuous collapse of the West, but by the growing economic, technological, and therefore military, power of the rest of the world. In principle, the West has no reason to fear the rise of the rest, as the United States and Europe still maintain an overwhelming deterrence, including nuclear deterrence, against any military threat from the outside. The West is bemoaning its loss of relative status—the ability to dictate to others—not any real military insecurity.

Nothing is going to restore Western hegemony in the coming years—no military victory, technological advance, or economic leverage. The rise of advanced military, technological, economic, and financial capacities to Asia and beyond, is unstoppable (and of course should not be stopped, since it signifies a world that is fairer and more prosperous than the preceding Western-dominated world). Yet, the end of Western hegemony does not mean a new Chinese, Indian, or Asian hegemony. There are simply too many power centers—the United States, the EU, China, Russia, India, the African Union, etc.—and too much capacity and diversity to enable any other hegemon to replace the Western-led world order. We have arrived, after centuries of Western dominance, to a world beyond hegemony.

This new world, beyond hegemony, should be the starting point for the Summit of the Future. The United States, UK, and the EU should come to the Summit not in a vain attempt to sustain their hegemony (as Boris Johnson fantasizes), or equivalently, to protect America’s self-declared “rules-based order”—a vacuous expression that envisions the rules as determined by the United States alone. They should come as part of a new multipolar world looking to find solutions to profound ecological, technological, economic, and other challenges. The new order should be based on multilateralism and international law under a suitably reformed UN Charter.

As President of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN)—a worldwide network of more than 2,000 universities and think tanks dedicated to sustainable development generally and to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) specifically—I have the opportunity to discuss humanity’s future with university leaders, scientists, technologists, policymakers, and politicians around the world, with the goal of envisioning a future that is prosperous, fair, sustainable, and peaceful for all of the world, not for a privileged West or any other small part of the world. Based on these extensive discussions, the SDSN issued a Statement on the Summit of the Future, responding to the five main “Chapters” for decisionmaking at the Summit: (1) achieving sustainable development; (2) ensuring global peace; (3) governing the cutting-edge technologies; (4) educating young people for our new world; and (5) reforming the UN institutions to make them fit for the post-hegemonic balance of the twenty-first century.

Here is a summary of the core recommendations of the SDSN.

Achieving Sustainable Development

The SDG Agenda should remain the core of global cooperation to 2050.

The SDGs were initially set for the fifteen-year period between 2016 and 2030, following the fifteen-year period of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). It is clear that the SDGs will not be achieved in the original time frame. We strongly urge that the SOTF recognize the pivotal role of the SDGs in aligning national, regional and global policies, and commit to the SDG framework until 2050, so as to reinforce the efforts already underway and recognize the time horizon needed to reorient the world economy to sustainable development. The new horizon of 2050 does not mean a slackening of effort. Rather, it means improved long-term planning to achieve highly ambitious 2050 goals and milestones on the way to 2050.

The Sustainable Development agenda should be properly financed.

All evidence developed by academia, the Bretton Woods system, and UN institutions is that there remains a massive shortfall in the pace of investments needed for the poorer nations to achieve the SDGs. In order to mobilize the needed investment flows for human and infrastructure capital, the global financial architecture must be reformed and made fit for sustainable development. The major objective is to ensure that the poorer countries have adequate financing, both from domestic and external sources, and at sufficient quality in terms of the cost of capital and the maturity of loans, to scale up the investments required to achieve the SDGs.

1.3 Countries and regions should produce medium-term sustainable development strategies

Sustainable Development in general and the SDGs specifically, require long-term public investment plans, transformation pathways, and a mission orientation to provide the public goods and services required to achieve the SDGs. For this purpose, all nations and regions need medium-term strategies to achieve the SDGs. These strategies, with a horizon to the year 2050, and in some cases beyond, should provide an integrated framework for local, national, and regional investments to achieve the SDGs, and for the technological transformations needed to achieve green, digital, and inclusive societies.

Achieving International Peace and Security

2.1 The core principles of non-intervention should be reinforced and extended.

The greatest threat to global peace is the interference by one nation in the internal affairs of another nation against the letter and spirit of the UN Charter. Such interference, in the form of wars, military coercion, covert regime-change operations, cyberwarfare, information warfare, political manipulation and financing, and unilateral coercive measures (financial, economic, trade, and technological), all violate the UN Charter and generate untold international tensions, violence, conflict, and war.

For this reason, the UN member states should resolve to end illegal measures of intervention by any nation (or group of nations) in the internal affairs of another nation or group of nations. The principles of non-intervention, enshrined in the UN Charter, UN General Assembly Resolutions, and international law, should be reinforced along the following lines.

First, no nation should interfere in the politics of any other country through the funding or other support of political parties, movements, or candidates.

Second, no nation or group of nations should deploy unilateral coercive measures, as recognized repeatedly by the UN General Assembly.

Third, in a world operating under the UN Charter, there is no need for nations to permanently station military forces in foreign countries other than according to UN Security Council decisions. Existing overseas military bases should be reduced dramatically in number with the aim of phasing out and eliminating overseas military bases over the course of the next 20 years.

2.2 The UN Security Council and other UN agencies should be strengthened to keep the peace and sustain the security of UN member states.

The UN Security Council should be reformed, expanded, and empowered to keep the peace under the UN Charter. Reform of the structure of the UN Security Council is described in Section 5 below. Here we emphasize the enhanced power and tools of the UN Security Council, including super-majority voting within the Security Council to overcome the veto by one member; the power to ban the international flow of weapons to conflict zones; strengthened mediation and arbitration services; and enhanced funding of peacebuilding operations, especially in low-income settings.

In addition to the Security Council, other key instrumentalities of global peacekeeping, human rights, and international law should be strengthened. These include the authority and independence of the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court, the functionality and support for UN-based humanitarian assistance especially in war zones, and the role of the UN Human Rights Council in defending and promoting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

2.3 The nuclear powers should return to the process of nuclear disarmament.

The greatest danger to global survival remains thermonuclear war. In this regard, the 10 nations with nuclear weapons have an urgent responsibility to abide by the non-proliferation treaty (NPT) mandate under Article VI “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” All nations, and especially the nuclear powers, should ratify and comply with the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Governing Cutting-Edge Technologies

3.1 Enhancing the multilateral governance of technological risks.

The world is experiencing unprecedented advances in the power, sophistication, and risks of advanced technologies across a range of sciences, technologies, and applications. These include biotechnology, including the ability to enhance pathogens and create new forms of life; artificial intelligence, including the potential for pervasive surveillance, spying, addiction, autonomous weapons, deep fakes, and cyberwarfare; nuclear weapons, notably the emergence of yet more powerful and destructive weapons and their deployment outside of international controls; and geoengineering, for example proposals to alter the chemical composition of the atmosphere and oceans, or to deflect solar radiation, in response to anthropogenic climate change.

We call on the UN General Assembly to establish urgent processes of global oversight of each class of cutting-edge technologies, including mandates to relevant UN agencies to report annually to the UN General Assembly on these technological developments, including their potential threats and requirements of regulatory oversight.

3.2 Universal access to vital technologies.

In the spirit of Section 3.1, we also call upon the UN General Assembly to establish and support global and regional centers of excellence, training, and production to ensure that all parts of the world are empowered to participate in the research and development, production, and regulatory oversight of advanced technologies that actually support sustainable development (rather than hyper-militarization). Universities in all regions of the world should train and nurture the next generation of outstanding engineers and scientists needed to drive sustainable development, with expertise in structural transformations in energy, industry, agriculture, and the built environment. Africa in particular should be supported to build world-class universities in the coming years.

3.3 Universal access to R&D capacities and platforms.

More than ever, we need open science for scientists in poorer countries and regions, including universal free access to scientific and technical publications, to ensure the fair and inclusive access to the advanced technological knowledge and expertise that will shape global economy and global society in the twenty-first century.

Educating Youth for Sustainable Development

We call on the Summit of the Future to prioritize the access of every child on the planet to the core investments in their human capital, and to create new modalities of global long-term financing to ensure that the human right of every child to quality primary and secondary education, nutrition, and healthcare is fulfilled no later than 2030.

4.2 Universal education for sustainable development and global citizenship (Paideia).

In adopting the SDGs, the UN member states wisely recognized the need to educate the world’s children in the challenges of sustainable development. They did this in adopting Target 4.7 of the SDGs:

“4.7 By 2030 ensure all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including among others through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development”

Target 4.7 is, in effect, the call for a twenty-first-century paideia, the ancient Greek concept of the core knowledge, virtues, and skills that should be attained by all citizens of the Polis. Today, we have a global polis—a global citizenry—that must be equipped to foster and promote the values of sustainable development and the respect of human rights throughout the world. We call on the Summit of the Future to reinforce Target 4.7 and bring it to life in education for sustainable development around the world. This includes not only an updated and upgraded curriculum at all levels of education, but training at all stages of the life-cycle in the technical and ethical skills needed for a green, digital, and sustainable economy in an interconnected world.

4.3 Council of Youth and Future Generations

The empowerment of youth, by training, education, mentorship, and participation in public deliberations, can foster a new generation that is committed to sustainable development, peace, and global cooperation. A new UN Council of Youth and Future Generations can strengthen the UN’s activities in training and empowering young people and can provide a vital global voice of youth to today’s complex challenges.

Transforming Global Governance Under the UN Charter

5.1 There should be the establishment of a UN Parliamentary Assembly.

Around the world, civil society, scholars, and citizens have called for strengthening global institutions by establishing representation of “We the Peoples” in the UN. We propose as a first instance to establish a “UN Parliamentary Assembly” as a subsidiary body of the UN General Assembly according to Article XXII of the UN Charter (“The General Assembly may establish such subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for the performance of its functions.”). The new UN Parliamentary Assembly would be constituted by representative members of national parliaments, upon principles of representation established by the UN General Assembly.

5.2 Other UN subsidiary bodies should be established.

Invoking the powers under Article XXII, the UN General Assembly should establish new subsidiary chambers as needed to support the processes of sustainable development, and the representativeness of UN institutions. The new chambers might include, inter alia:

A Council of the Regions to enable representation of regional bodies such as ASEAN, the EU, African Union, Eurasian Economic Union, and others;

A Council of Cities to enable representation of cities and other sub-national jurisdictions;

A Council of Indigenous Peoples to represent the estimated 400 million indigenous peoples of the world;

A Council of Culture, Religion, and Civilization’ to promote a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation for cultural diversity, religion, and civilizations;

A Council of Youth and Future Generations to represent the needs and aspirations of today’s youth and of generations to come (see Section 4.3 above);

A Council on the Anthropocene to support and enhance the work of the UN agencies in fulfilling the aims of the Multilateral Environmental Agreements (including the Paris Climate Agreement and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework) and the environmental objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals.

5.3 The UN Security Council Should Be Reformed in Membership and Powers

We call on the UN Security Council and the UN General Assembly to adopt urgently needed reforms of the Security Council structure and processes. These should include: (1) the addition of India as a permanent member, considering that India represents no less than 18 percent of humanity, the third largest economy in the world at purchasing-power parity, and other attributes signifying India’s global reach in economy, technology, and geopolitical affairs; (2) the adoption of procedures to override a veto by a super-majority (perhaps of three-quarters of the votes); (3) an expansion and rebalancing of total seats to ensure that all regions of the world are better represented relative to their population shares; and (4) the adoption of new tools for addressing threats to the peace, as outlined in Section 2.2.

Reflection & Reconsideration

The most fundamental principle for our new world system must be mutual respect among nations. The world faces profound and unprecedented challenges—environmental destruction, widespread political instability, the weaponization of cutting-edge technologies, and the dramatic widening of inequalities of wealth and power—that can only be addressed through peaceful cooperation among nations. Yet, despite the urgency of cooperation, we are drifting towards wider war.

The UN is very much a work in progress. It is the creation of a very different world, one that was dominated by the United States in the intermediate aftermath of World War II. At 79 years old, the UN is still an infant in the age-old challenge of good governance and international statecraft. In a world filled to the brim with ever more powerful weaponry, especially nuclear weaponry, solving the challenge of peaceful cooperation is the most vital challenge of all.

The Summit of the Future is therefore a key moment for reflection and reconsideration on how to govern our new multipolar world, at a time of unprecedented challenges facing humanity. The world’s challenges will certainly not be solved at the September conference, but the Summit of the Future can nevertheless mark a vital starting point for a new global governance in which all regions of the world contribute cooperatively to the global common good.

Jeffrey D. Sachs is a world-renowned economics professor, bestselling author, innovative educator, and global leader in sustainable development. Originally published on the Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development.

Related:

China's GDI, GSI, and GCI foster global cooperation, address urgent challenges

Related posts:

UN Pact for the Future builds up a hard-won consensus

Pope Francis, power rivalry and the global order

China recently organized the country's largest comprehensive emergency rescue aviation exercise, demonstrating the systematic achievements in its independent ...

China recently organized the country's largest comprehensive emergency rescue aviation exercise, demonstrating the systematic achievements in its independent ...