Billionaire Kuok says empire can last generations

When billionaire

Robert Kuok

introduced a luxury hotel brand in 1971, he named it Shangri-La, after

the fictional utopia in which inhabitants enjoy unheard-of longevity.

Ensconced

in his executive suite 32 floors above Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbor --

the room decorated with a pair of elephant tusks gifted by the late

Tunku Abdul Rahman, the first prime minister of Malaysia -- the world’s

38th-richest person appears to have defied the aging process himself.

Kuok had accumulated a fortune of $19.4 billion as of Jan. 31, according to the

Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Trim, dapper and straight backed at 89, he shows no signs of stopping

there, Bloomberg Markets magazine will report in its March issue

A waiter serves a customer at the bar at the Shangri-La Hotel in Paris. Photographer: Eric Piermont/AFP/Getty Images

This year, the media-shy Malaysian-born magnate will likely open his

71st sumptuously appointed Shangri-La. Six of them are scheduled to be

opened in the third quarter alone, including one perched in

the Shard, the 72-story London skyscraper that’s the tallest office building in Western Europe.

Meanwhile,

the public and private companies his family controls continue to pump

money into his ancestral homeland, China, where his investments range

from Beijing’s tallest building to cooking oil brands that have gained a

50 percent market share in the world’s most populous nation.

Robert Kuok shovels dirt at a

ground breaking ceremony for the Shangri-La Asia Ltd.'s new hotel in

Guangzhou on Feb. 26, 2004. Through the unlisted family-owned holding

company, Kerry Group Ltd., which he chairs, Kuok controls listed

enterprises with a total market value of about $35 billion.

Photographer: Grischa Rueschendorf/Bloomberg

Robert Kuok shovels dirt at a

ground breaking ceremony for the Shangri-La Asia Ltd.'s new hotel in

Guangzhou on Feb. 26, 2004. Through the unlisted family-owned holding

company, Kerry Group Ltd., which he chairs, Kuok controls listed

enterprises with a total market value of about $35 billion.

Photographer: Grischa Rueschendorf/Bloomberg

‘Personally Powerful’

One of Kuok’s companies, Singapore-listed

Wilmar International Ltd. (WIL), is the world’s biggest processor of

palm oil and eighth-biggest sugar producer.

Wilmar International Ltd.’s

cooking oil brands —led by Jin Long Yu, meaning Golden Dragon Fish, seen

in this photo — grease half of China’s woks and generate 48 percent of

the company's revenue. Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Western Europe's tallest office

building will be home to one of Robert Kuok's new luxury Shangri-La

hotels. Six are scheduled to be opened worldwide during the third

quarter. Photographer: Jumper/Getty Images

Western Europe's tallest office

building will be home to one of Robert Kuok's new luxury Shangri-La

hotels. Six are scheduled to be opened worldwide during the third

quarter. Photographer: Jumper/Getty Images

Others

operate shipping and logistics businesses, a property portfolio

stretching from Paris to Sydney and East Asia’s most influential

English-language newspaper, the Hong Kong-based

South China Morning Post.

“He’s

so vital, so active and continues to be so personally powerful,” says

Timothy Dattels, San Francisco-based senior partner at U.S. buyout firm

TPG Capital LP and a director of Kuok’s Hong Kong-listed

Shangri-La Asia (69) Ltd. “I can’t imagine a day without him at the top.”

Others

can, which is why the question of succession looms over the Kuok empire

as the patriarch prepares to mark his 90th birthday in October.

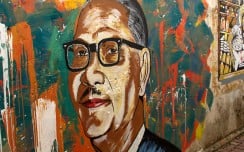

The world’s 39th-richest person,

who named his Shangri-La hotel chain after the fictional utopia in which

inhabitants enjoy unheard-of longevity, is trim, dapper and straight

backed at 89. The public and private companies his family controls

include investments in Beijing’s tallest building and cooking oil brands

that have gained a 50 percent market share in China. Photographer:

Grischa Rueschendorf/Bloomberg

Through

the unlisted family-owned holding company, Kerry Group Ltd., which he

chairs, Kuok controls listed enterprises with a total market value of

about $40 billion.

As it stands, the family enterprises are seeking to recover from a rocky 2012 that featured some sharp share-price and profit

drops.

First Interview

In his first interview with Western news

media in 16 years, Kuok, who has eight children and numerous other

relatives sprinkled through his executive ranks, says he won’t be

worried when that day eventually comes.

“Everything on earth is

dynamic,” he says in perfectly enunciated English. “I can only give my

children a message, not money. If they follow it, we can go another

three or four generations.”

Relatives run the most important of the Kuok businesses.

Kuok’s second son, Kuok Khoon Ean, 57, heads Shangri-La Asia, of which the family owns 50 percent.

A

nephew, Kuok Khoon Hong, 63, co-founded and chairs Wilmar

International, the largest Kuok-controlled company, with a market value

of almost $20 billion, in which the Kuok family controls a 32 percent

stake.

A daughter, Kuok Hui Kwong, 35, is executive director of

SCMP Group Ltd., publisher of the 109-year-old South China Morning Post,

which Kuok took control of in 1993, when he paid

Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. $349 million for a 35 percent stake.

Pedestrians walk past the

headquarters of the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong. Robert Kuok's

daughter, Kuok Hui Kwong, 35, is executive director of SCMP Group Ltd.,

which Robert Kuok took control of in 1993, when he paid Rupert

Murdoch’s News Corp. $349 million for a 35 percent stake. Source:

Imaginechina

Pedestrians walk past the

headquarters of the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong. Robert Kuok's

daughter, Kuok Hui Kwong, 35, is executive director of SCMP Group Ltd.,

which Robert Kuok took control of in 1993, when he paid Rupert

Murdoch’s News Corp. $349 million for a 35 percent stake. Source:

Imaginechina

Focus Attention

As to who will succeed the master, most

investors in Kuok enterprises focus attention on his eldest son, Kuok

Khoon Chen, 58, who’s known as Beau.

Robert declined to confirm that Beau, who is deputy chairman of Kerry Group, will succeed him.

The development site for the

Shangri-La Residences stands in Yangon, Myanmar on Nov. 20, 2012.

Photographer: Dario Pignatelli/Bloomberg

The development site for the

Shangri-La Residences stands in Yangon, Myanmar on Nov. 20, 2012.

Photographer: Dario Pignatelli/Bloomberg

“Newshounds

like excitement in their stories, whereas leadership of a business

group is always a serious matter, and it would be wrong to put in

writing any kind of assumption,” Kuok wrote in an e-mail following the

interview.

A visitor looks out the window of

Island Shangri-La hotel, owned by Shangri-La Asia Ltd., in Hong Kong.

Robert Kuok’s second son, Kuok Khoon Ean, 57, heads Shangri-La Asia, of

which the family owns 50 percent. Photographer: Marco Flagg/Bloomberg

A visitor looks out the window of

Island Shangri-La hotel, owned by Shangri-La Asia Ltd., in Hong Kong.

Robert Kuok’s second son, Kuok Khoon Ean, 57, heads Shangri-La Asia, of

which the family owns 50 percent. Photographer: Marco Flagg/Bloomberg

Beau, who’s worked in his father’s businesses since 1978, is chairman of

Kerry Properties Ltd. (683)

The firm, 55 percent owned by Kerry Group, develops luxury apartments,

shopping malls and offices mostly in China and Hong Kong.

“I know

Beau, and he has a good team,” says Peter Churchouse, founder of Hong

Kong-based property investor Portwood Capital Ltd. “But you have to

wonder whether the second and third generations have the entrepreneurial

and trading instincts that the father has.”

‘China Watcher’

The father’s instincts were honed over

decades of personal and historical turbulence inconceivable to the

generation vying to take over the family business.

That

experience helped him become one of the first -- and best-connected --

foreign investors in China following Mao Zedong’s communist revolution.

“Robert is the best China watcher in the business,” says

Simon Murray,

chairman of Glencore International Plc, the world’s biggest

commodities-trading company. “He understands the steel backbone of the

Communist Party, but while other Hong Kong tycoons tend to be hugely

subservient to Beijing, he is in no way obsequious.”

Robert Kuok, chairman of Kerry

Group Ltd., holds a trophy during the 2012 CCTV China Economic Person of

The Year award at China Central Television in Beijing on Dec. 12, 2012.

Source: ChinaFotoPress via Getty Images

For all of Kuok’s prowess, 2012 was a tumultuous year for investors in his enterprises.

While Kerry Properties stock surged 57 percent in Hong Kong last year -- more than double the increase in the

Hang Seng Index -- Wilmar International’s shares plummeted 33 percent, making it the worst performer in Singapore’s

Straits Times Index. (FSSTI)

‘A Fraction’

The

plunge wiped the equivalent of more than $8 billion from the company’s

market value -- and almost $3 billion from the family’s fortune. This

year, Wilmar’s share price has rebounded, rising 14 percent in January.

In

any event, Kuok disputes Bloomberg’s valuation of his personal wealth

at $19.4 billion; he says it’s “a fraction” of that amount, though he

does not volunteer an alternative figure.

Wilmar’s woes stem from

its massive exposure to China, where its cooking oil brands -- led by

Jin Long Yu, meaning Golden Dragon Fish -- grease half the country’s

woks and where it gets 48 percent of its revenue.

Beijing limited price increases on edible oils during most of 2011 and part of 2012, Wilmar said at the time.

Furthermore,

the rising cost of soybeans, which Wilmar uses to produce cooking oil,

hit a record $17.89 a bushel in September, squeezing earnings.

Rough Ride

In the first nine months of 2012, profit fell 29 percent to $779 million from $1.1 billion a year earlier.

Kuok’s Hong Kong-based companies have had a rough ride since the global financial crisis.

As

of Jan. 31, Shangri-La Asia and Kerry properties shares were both down

19 percent compared with a 1 percent increase in the Hang Seng Index.

Asked about such

underperformance (583), Kuok says enigmatically, “It is right and proper for the investor to like or dislike a share.”

Underperformance

isn’t the only problem at SCMP Group, whose share price had declined 69

percent as of Jan. 30 since Kuok acquired it. In 19 years, the South

China Morning Post has churned through 11 editors, including one who

served twice.

And although Kuok says his news executives publish

without fear or favor, present and former staff members have publicly

complained that the paper sometimes self-censors stories it thinks the

Chinese government wouldn’t like.

‘Toned Down’

“Under

his ownership, criticism of China has been toned down,” says David

Plott, managing editor of Global Asia, a Seoul-based quarterly. “And if

you look at the turnover of editors, it tells you one of two things:

either Robert Kuok doesn’t know what he wants or he knows what he wants

and he hasn’t gotten it.”

If that’s true, it might be a first for Kuok, whose life story has been one of single-minded achievement.

The

son of Chinese immigrants who had settled in British- controlled

Malaya, Robert Kuok Hock Nien -- his full name -- grew up speaking his

parents’ Chinese Fuzhou dialect, English and even Japanese during

Japan’s wartime occupation of the region.

Significantly, given the role China would play in Robert’s life, his

mother encouraged him to achieve fluency in Mandarin and embrace his

Chinese heritage.

Kuok’s

parents ran a shop that sold rice, sugar and flour. Kuok recalls living

with the smell of his addicted father’s opium pipe in his nostrils.

Family Business

Still,

there was enough money for Robert to progress from a local English

school to Raffles College in Singapore, where fellow students included

Lee Kuan Yew, later the founder of modern Singapore.

Kuok

never finished his studies. In 1941, Japanese troops stormed through

the Malay Peninsula and in February 1942 captured Singapore. Kuok took a

job with Mitsubishi Corp. With Japan’s defeat in 1945, his family

resumed doing business under the British.

In 1949, after his

father died, Robert; a brother, Philip; and other relatives founded Kuok

Bros. Sdn., which later specialized in sugar refining.

Philip

went on to become a Malaysian diplomat, and a second, much-admired

brother, William, took an entirely different path again by joining the

communist revolt against colonial rule. In 1953, William Kuok was killed

by British troops in a jungle ambush.

Furtive Rendezvous

Robert

Kuok, by contrast, used his English-language skills on visits to London

to learn the sugar business while remaining based in Malaysia and later

Singapore.

During the

Cold War, he traded with both Western and communist blocs, meeting Cuba’s

Fidel Castro and doing business with China’s Mao from as early as 1959.

In

1973, with China in the grip of the Cultural Revolution, Kuok was

summoned to Hong Kong for a furtive rendezvous with two of Mao’s trade

officials.

They confided that China was facing a sugar shortage.

Kuok stepped into the breach, transferring his headquarters to Hong Kong

that year.

It was a prescient move. In 1976, Mao died, and in 1978,

Deng Xiaoping tore down the so-called Bamboo Curtain, initiating reforms that sparked 34 years of surging

economic growth.

In

1984, Kuok opened his first Shangri-La on the mainland. The following

year, he partnered with China’s foreign trade ministry to begin building

the

China World Trade Center (600007) in Beijing.

Enduring Mystery

In

1988, at his nephew Khoon Hong’s suggestion, he branched out into

edible oils. By 1993, Coca-Cola Co. was impressed enough with Kuok’s

China connections to form a bottling joint venture with him.

That

lasted until 2008, when Coke bought back Kerry Group’s stake for an

undisclosed amount, both companies pronouncing the outcome a success.

The

family’s history of that period harbors an enduring mystery: a 16-year

parting of the ways between Robert and Khoon Hong, who in 1991 left the

Kuok Group to set up Wilmar with Indonesian entrepreneur Martua Sitorus.

It wasn’t until 2007 that Robert acquired a 32 percent stake in

Wilmar and injected most of his agribusiness into it. Neither Robert nor

his nephew would discuss the split.

For all his triumphs in the

capitalist world, Robert Kuok says the biggest influences on his life

were his devoutly Buddhist mother and his communist revolutionary

brother, William.

‘Good Boys’

“Otherwise, probably I

would have been an arrogant middle- class Chinese, only caring about

materialism, worldly pleasures and fleshpot pleasures,” Kuok says, his

moist eyes betraying a momentary sadness. “When I am tempted, I think of

what William went through. He sacrificed his life trying to help the

underprivileged.”

Kuok says he has tried to pass on those values

by not cocooning his children in privilege. Nor, he adds, does he place

much emphasis on scholastic qualifications, including MBA degrees, when

hiring senior staff.

Beau Kuok earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from

Monash University in Melbourne; Ean holds a similar qualification from the

University of Nottingham in England. Kuok describes Beau and Ean as “good boys.”

Among members of the extended family, Kuok speaks highly of Khoon Hong, his nephew at Wilmar.

‘Stupid Ones’- Perils of succession

“There

are stupid ones, there are mean ones, but he’s one of the cleverest,”

Robert Kuok says. None of the second- generation Kuoks would comment for

this article. Kuok says they make their own decisions. “I never control

my children,” he says. “We are a very liberal, democratic family.”

The perils of succession are acute in Kuok’s bailiwick, according to researchers at the

Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Their

study of 250 family-controlled businesses in Hong Kong, Singapore and

Taiwan from 1987 to 2005 shows that stocks typically plunged 60 percent

over an eight-year period before, during and after a founder’s

relinquishing control.

Joseph Fan, the finance professor who led

the research, attributes this wealth destruction to the inability of the

patriarch to pass on, even to family members, his most valuable,

intangible assets, including relationships with governments and banks.

“The founder is the key asset,” Fan says.

That’s why, Fan says,

so many tycoons remain at the helm of their businesses well into their

80s and don’t disclose succession plans.

Octogenarian Rivals

Last

year, following investor concerns over feuds that have split the second

generation of some of Hong Kong’s most prominent families, two of

Kuok’s octogenarian billionaire rivals in the property business,

Li Ka-shing

of Cheung Kong Holdings Ltd. and Lee Shau-kee of Henderson Land

Development Co., finally disclosed which of their progeny would

eventually take control.

TPG Capital’s Dattels says succession isn’t a concern when it comes to the Kuok businesses.

“There’s

only one Robert Kuok, there’s no doubt,” he says. “But he has instilled

his business philosophy deep into the family. With what he has built,

they are well set to continue, whatever happens.”

Back at his

Hong Kong headquarters, Kuok asks an assistant to bring him a favorite

quotation. Written by his mother in Chinese and engraved on a steel

plate, the aphorism reads:

“If my children and grandchildren can

be like me, then they don’t require material inheritance. But if they

are not like me, then of what use is my wealth to them?”

Those

words beg the question investors in Kuok’s far-flung businesses are

asking now more than ever: How like Robert Kuok are his heirs? - Bloomberg